About Me

I'm Thibaud, a French guy currently living in Brussels, Belgium.

In no particular order, I am

- A general food snob (from being French)

- A coffee, pasta, and pizza snob (from living in Italy)

- A Beer snob (from living in Belgium)

- An inveterate cyclist and bike-packer

- A linux user, with a bad addiction to tiling window managers

I write content here, to make it easily accessible for myself in the future, but also to improve my technical writing. As a software person, I spend a significant fraction of my time writing documentation for customers and peers. This site gives me a chance to hone my skills with a different voice.

Outside of Work

Living in Milan, the mountains were just an hour away. A train ride would take you to the foot of a mountain, another train on the other side would take you home. This made hiking an every-week activity.

A view of Lake Como, from the mountains between Como and Lecco.

Upon moving to Brussels, mountains became much more scarce. A two hour drive just to get to the first foothills of the Ardennes was much less appealing. Instead I bought a bicycle and discovered the joys of long-distance cycling. I've criss-crossed Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, ... and intend to continue exploring Europe on two wheels.

Cycling from Liege to Brussels, the day after the biggest snowfall in years.

My Career So Far

I discovered the joy of programming at University, during an "Introduction to C" class in my first semester. From there I learned C++ and Python in my free time, and never stopped programming. Somehow, I made it into a career.

For my master thesis, "Data-Driven Attitude Control Design For Multirotor UAVs", I developed an attitude controller for a quadcopter using data-driven method. Specifically I used Virtual Reference Feedback Tuning to synthesise a pitch control loop for the vehicle.

Getting started: Nearlab

I studied controls theory at Politecnico di Milano. As I was finishing my masters, and struggling to finish my thesis, a friend who was doing a PhD told me his lab (Nearlab) had received a surgical robot, and that they were looking for somebody to figure it out. It wasn't a job, or an academic course, I just showed up with my laptop and started reading documentation.

A few months later, the principal investigator (the head of the lab) offered me a real job, doing the same thing, but for actual money.

My office at Nearlab, two computers, one giant 4-armed robot, and one operator console in a cramped room.

I was working on SMARTSurg a project that was supposed to develop a next generation surgical robotics system to reduce the cognitive load of surgeons, shorten their training time, and improve patient outcomes. In practice the fundamental design of the system was flawed and the expected outcomes never materialised.

For me though, it was a great playground! Discovering actual hardware, complex software systems, and trying not break it all. I spent time reverse-engineering connector pinouts, trying to calibrate a long stereo-endoscope with the worst distortion I've ever encountered, and deciphering code written by other researchers in the lab. Most of the work I did is open-source at gitlab.com/polimi-dvrk. Reading through it, I'm still proud of the work I did on libdecklink a library to interface with BlackMagic video grabbers.

The lab was also my first exposure to mentoring students, and guiding them through projects. We made a dataset of stereo images of pig-organs (bought from a local butcher), worked on hand-eye calibration for the robot and more.

After a year, my contract expired, and I moved to Belgium.

Discovering Space: Space Applications Services

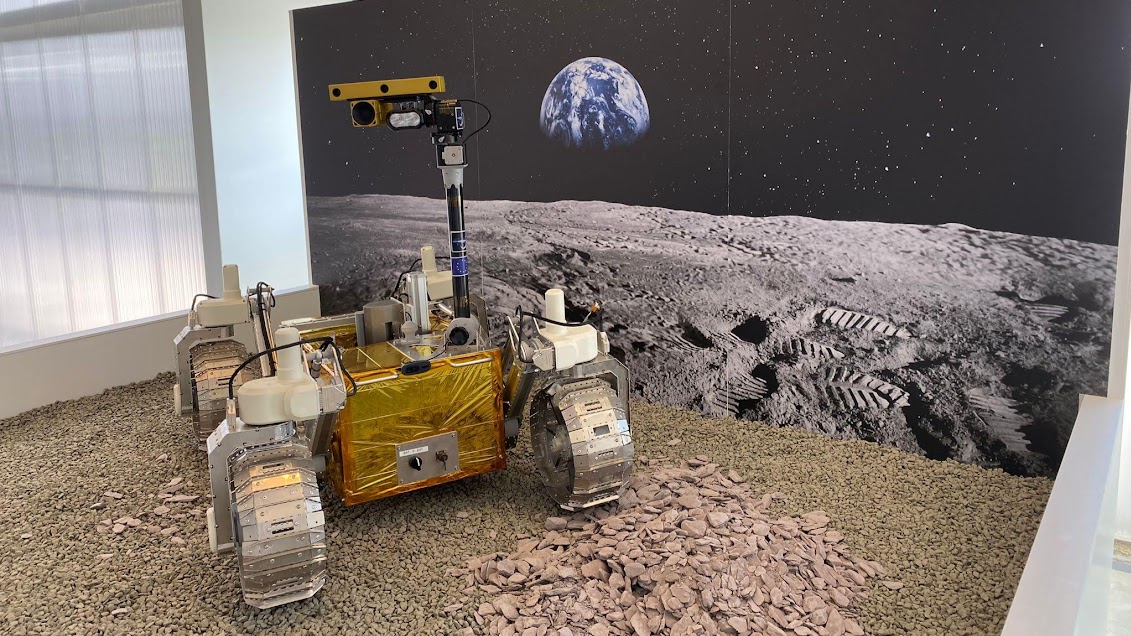

Arriving in Belgium, I started working at Space Applications Services. I was shown a robot, and told it needed to be driving around in a month. It took me more than a month, but it did drive. This was LUVMI, the lovable lunar rover. We embarked on a second version, learning from our mistakes, and this became LUVMI-X.

After stripping down the original LUVMI to remove parts that could be re-used, and cleaning up the exterior, we took the rover to a museum where it stayed for a few years.

The LUVMI rover, on it's display stand, at the Astropolis museum in Oostende, Belgium.

When I wasn't working on the rover, I helped develop HOTDOCK, a mating device for satellites, making the firmware for the first demo version we took the to the International Aeronautical Congress in Washington. I spent most of the week under a table, debugging the demo, instead of visiting the city.

When COVID hit, I was locked at home working on the navigation system for a satellite servicing mission, using fiducial markers to determine the position of the satellite that needed to be serviced.

After a 4 years there, I started to yearn for commercial work, and not just one-off research projects.

Moving Again: European Space Agency

After years of living in French-speaking Brussels, I wanted to move to a country where I did not speak the language. An opportunity for the Dubai space agency came up, but stalled mysteriously, I turned down an opportunity with Ascento working on their cute robots, and finally found a position I wanted: working in the Human Robot Interaction Lab at the European Space Agency. This lab is responsible for impressive controls demo, showing humans in the International Space Station working with robots on the ground.

Operating the Interact rover from the mockup of the Columbus Module at ESTEC.

My time there started inauspiciously. The lab has 2 full-time software engineers and a gaggle of trainees. I was replacing one, and the other was leaving in a month ... I hit the ground running and tried to patch together an understanding of the systems. I became a part-time sysadmin, and dived into technology stacks and programming languages that were unfamiliar to me:

- I learned some Go to fix bugs in the software that provisioned the computers we used in the International Space Station.

- I learned enough about Buildroot to try and slim down the Linux image we ran our software on.

- I learned Simulink, and DDS, and the robot control stack we inherited from DLR the German Aerospace Agency.

However, we were a pair of engineers in a place that desperately needed researchers instead. So, I was pushed out, and I moved into industry

Discovering Industry: AAC Hyperion

Looking for a new job, I decided that for once, I should find a job in the country I live in. The space industry in the Netherlands is quite small so that only left me with a handful of options.

I somehow got a position at AAC Hyperion after pitching myself by explaining that I had none of the required skills, but apparently making a good enough case that my skills were just as relevant. This time around, I was working for a private company, with private customers, not on abstract research projects.

After starting, I quickly discovered that any notions I might have had about the software standards of aerospace were misplaced. Not only was there no software standard in sight (no MISRA, no ECSS-E-ST-40C), there was no continuous integration in sight!

I spent time building the continuous integration setup from scratch (from buying servers, to actually building pipelines), and progressively working my way through a backlog of software quality tasks, and building tooling where required.

- What code formatting rules do we use?

- What static analysis do we use?

- How do we handle testing?

- How do we handle releases?

- How do we handle dependencies?

After a year, I moved back to Brussels to move in with my partner, and commuted to the Netherlands a few days a week. Eventually, I left, to take a job in Belgium, closer to home. In the meantime, I had worked on reaction wheels, laser communications systems, sun sensors, and attitude determination and control systems (the thing that points the satellite)! By the end of it, I had a new respect for the challenges of actually producing hardware in volume.

The Next Step: Under Wraps

All will be revealed soon. After leaving Hyperion, I took a few months to look for a job in Belgium, and used the time to work on projects I had abandoned long ago for lack of time. One of these, was this very website. I took the time to refresh it and start populating it with content again.

Social Links

If you'd like to find out more about me you can: